Back to GanjaTron's site

Back to GanjaTron's siteStereo Realist

The Stereo Realist is perhaps (along with the Viewmaster) the most ubiquitous stereo camera around, having sold some 250000 units worldwide. Remarkably, it still sees widespread use by 3D enthusiasts over half a century after its introduction to the market! This is largely attributed to its rugged and simple design but also to the cult following that has grown around this camera over the decades. It was this camera that got me acquainted with stereo photography, and although I don't consider it a go-anywhere camera for daily use, it does its somewhat specialised job nicely given the right motifs.

History

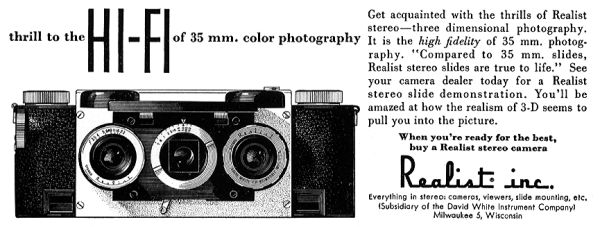

Stereo photography is as old as conventional photography itself, but always remained a niche on the grounds that it was considered no more than a gimmick by most photographers. Nevertheless, stereo photography flourished during the late 19th and early 20th centuries. The Stereo Realist was one of the first cameras to usher in the post-WW2 3D revival that lasted well into the 50s. Introduced in 1947, it kept its place in the 3D niche until the early 70s with only minor modifications. It held its own against the competition because it was a real camera as opposed to the toys most of the competition produced with simplified focus and exposure settings, plastic bodies, crappy lens, etc. These latter characteristics emphasised the gimmicky, amateurish nature of 3D photography in the eyes of professional proponents of conventional photography. The Stereo Realist was an exception, offering a sturdy build and full control as with conventional cameras.

The Stereo Realist was the brainchild of Steton Rochwite, a newly hired young engineer at the David White Company, Milwaukee, specialising in surveying instruments. Photographic equipment was virgin territory for the company, and Rochwite apparently didn't follow any rigid specs nor break new ground when he designed the Realist, but rather tinkered around with existing 35mm camera technology and adapted it to stereo. The "garage workshop" nature of its conception is reflected in the Realist's appearance: functional, but ugly.

The Realist was aggressively promoted at the time with Hollywood celebrities posing with the camera in ads (figuring that movie people know all about cameras, duh). The most prominent of these was silent era comedian Harold Lloyd, who amassed a staggering archive of over 300000 3D photographs, some of which were published in his book "3D Hollywood" (edited by his granddaughter Suzanne Lloyd Hayes). It was this book that pointed me towards the Stereo Realist.

The Realist's 22x24mm image format became a standard for other subsequent stereo cameras and their accessories such as slide mounts, viewers, etc. Even today, more than 50 years after its inception, the format is still a recognised standard, and stereo nuts are still happily snapping away with their Realists.

Characteristics

The Stereo Realist is a typical American design: big and heavy, rugged and reliable, yet unsophisticated and even ugly. Kinda like an old Buick. Its body looks and feels like a brick, consisting almost entirely of brass and/or aluminium, with the exception of the Bakelite lensboard and cover bearing the Realist logo. Robustness is the overbearing quality of the Realist (IMHO making up for some of its deficiencies); stories circulate the internet of owners running them over with cars or using them as weapons in bar fights, with the camera allegedly coming out intact. Nah, I don't believe that either... :^)

The camera is equipped with the usual stuff you'd find on a conventional camera: aperture dials on the lens (coupled between both lens), shutter speed dial, focus knob, shutter release, film wind knobs, and a custom flashmount. But that's where the similarities end.

For starters, it has two lens (duh). A very small (and highly collectible) number were equipped with 4-element f/2.8 lens, while the 3-element (Cooke triplet) f/3.5 lens are far more common. Early Realists carried Kodak f/3.5 Ilex or f/2.8 Ektar lens, while later specimens were equipped with David White Anastigmats. The latter is very common, but its optical quality is actually pretty mediocre in my opinion, lacking sharpness and exhibiting noticeable flare and vignetting. Having said that, the lens on the Realist are probably still superior to some of the competition's.

The Realist actually has two finders: a split image ("military type" according to the manual!) rangefinder with windows flanking the lens housing and a separate finder located between the taking lens for image composition. The eyepieces for both are located on the back at the bottom. This is the most ridiculous concept I've ever seen on a camera, but it works somehow.

The shutter is a very simple metal plate with openings for both lens which slides behind the lensboard during exposure. The shutter dial is mounted around the finder lens and has settings for non-linear times down to 1/150 or 1/200 sec on f/3.5 and f/2.8 models, respectively. The shutter isn't particularly quiet but appears to be remarkably reliable. The shutter must be cocked manually for every exposure with the lever below the lensboard -- an anachronism even for postwar cameras.

The film transport is cumbersome at best: an indicator on the top turns red (danger, danger!) when an exposure has been made, subtly suggesting you might wanna advance the film. Of course, you can ignore it -- the Realist doesn't know (or care) about double exposures, and won't prevent you from making them. This is apparently because the shutter and transport mechanisms are not coupled in any way. A button on the back must be pressed to release the catch on the film wind and advance the film. The film counter is actually advanced automatically -- wow! But because you shouldn't be pampered too much, it has to be manually reset to 1 when loading the film by physically turning the counter. Naturally, you can also mess up your exposure count this way halfway through a roll. By a similar token, you can advance the film without even making an exposure. Look elsewhere if you want an intelligent camera... :^)

The focusing mechanism is also weird; the Realist uses backplane focusing, meaning that the film moves relative to the fixed lens, not vice versa as is more common. While this is a simple solution to simultaneous focus of both lens, it's not particularly conducive to film planarity and can slacken the film which often leads to some peripheral overlap in subsequent exposures. Not sure how accurate this mechanism is, particularly regarding simultaneous lens alignment.

The back of the camera covers its entire width and is held in place with a fairly primitive latch which quickly wears out, forming gaps which cause frequent light leaks. This is by far the most common problem with the Realist and can become very annoying. Several of my exposures have been ruined by light leaks, and I ended up sealing the edges around the back with black tape. This is such a common fault that many owners consider it a feature rather than a design flaw.

The Realist uses standard 35mm film and exposes 22x24mm pairs which are 2 exposures apart on the film roll. This implies a 2-way interleave for image pairs, which can be irritating when examining a film with many similar exposures.

Handling

In a nutshell: the Stereo Realist looks, feels, and operates like an anvil! It brims with idiosyncrasies which challenge the beginner. The procedure for making an exposure is ridiculous by modern standards:

- Flip open lens cover

- Set lens aperture (easier with one hand on each lens)

- Adjust shutter speed

- Cock the shutter (I always, always, always forget this, then wonder why nothing happens!)

- Squint through the rangefinder and adjust the focus

- Squint through the image finder and compose the pic

- Trip the shutter

- Release the winder catch

- Twiddle winder knob a several times (very annoying) until catch locks it into place again.

Squinting through the finders (actually more like tiny peepholes) at the bottom of the back means you're wandering around with a 3-lens camera glued to your forehead looking like, for want of a better word, a friggin' moron! Few cameras can do that. Really.

Holding the camera isn't straightforward either; beginners will often find themselves squinting into a pitch black rangefinder, only to discover they're obstructing its windows at the front of the camera! (Happened to me too). The camera should actually be held with fingers on the wind knobs and thumb on the bottom.

Furthermore, poor performance of the f/3.5 lens means large apertures should be avoided whenever possible. At the same time, small apertures must be avoided to avoid vignetting. I think f/8 is an optimal setting for these lens, but that can be a problem in poor lighting.

So after putting up with all this, what do get as payoff? Stunning, vivid, lifelike stereo pix. Infact, even the most mundane motifs take on a fascinating life of their own in stereo. However, most labs don't know how to handle films exposed with stereo cameras, so you're better off making prints or mounting the slides yourself. Particularly the autoprocessors in labs assume a standard 35mm frame when chopping films into strips, which will inevitably destroy films exposed with the Realist format. Most labs are capable of processing films in one piece though, otherwise you'll have to do your own processing too.

Pros

Cons

Links

Dr. T's Stereo Realist PageGuide to Classic Cameras: Stereo Realist

The Official Stereo Realist Site

Stereo Realist User Manual

Back to photo stuff

Back to GanjaTron's site

Back to GanjaTron's site